Who invented the index fund? A temporary (true) historical past of index funds

Pop quiz! If I asked you,” Who fabricated the indicator money ?” what would your answer be? I’ll bet most of you don’t know and don’t care. But those who do attend is very likely answer,” John Bogle, founder of The Vanguard Group .” And that’s what I would have answered more until a few weeks ago.

But, it turns out, this answer is false.

Yes, Bogle founded the first publicly-available index money. And yes, Bogle is responsible for popularizing and promoting index stores as the “common sense” investment answer for the average person. For this, he deserves much praise.

But Bogle did not invent index stores. In fact, for a long time he was opposed to the awfully theory of them!

Recently, while writing the investing assignment for my upcoming Audible course about the basics of financial independence, I witnessed myself deep down a rabbit opening. What started as a simple Google search to verify that Bogle was indeed the designer of index stores passed me to a” confidential autobiography” of which I’d been totally unaware.

In this article, I’ve done my best to assemble the bits and pieces I discovered while tracking down the descents of indicator funds. I’m sure I’ve made some mistakes here.( If you spot an error or be made aware of added info that should be included, descent me a line .)

Here then, is a brief history of index funds.

What are index funds ? An index fund is a low-cost, low-maintenance mutual fund designed to follow the rate waverings of a stock-market index, such as the S& P 500. They’re an excellent option for the average investor.

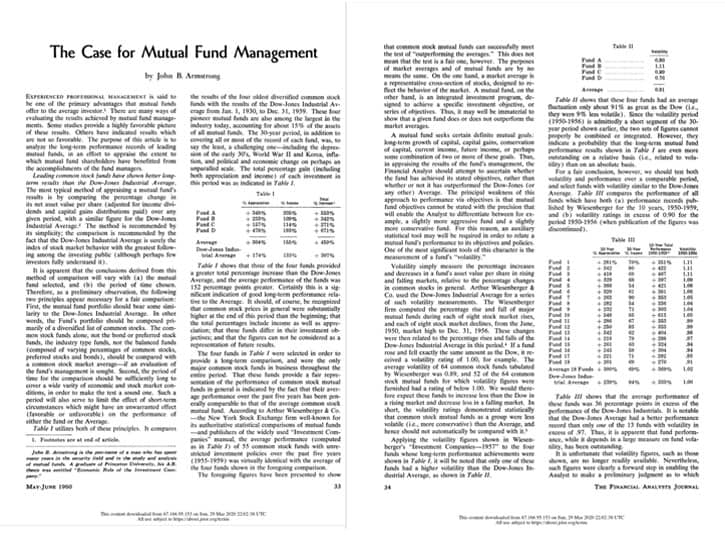

The Case for an Unmanaged Investment Company

In the January 1960 issue of the Financial Analysts Journal, Edward Renshaw and Paul Feldstein publicized an section entitled,” The Case for an Unmanaged Investment Company .”

Here’s how the paper began 😛 TAGEND

” The trouble of pick and oversight matters which was initially made a need for investment firms has so sprouted these institutions that today a contingency can be made for creating a new investment institution, what we have chosen to call an ” unmanaged investment company” — in other words a company dedicated to the task of following a representative average .”

The fundamental problem facing individual investors in 1960 was that there were too many mutual-fund business: over 250 of them. “Given so much choice,” the authors wrote,” it does not seem likely that the inexperienced investor or the person who needs term and information to supervise his own portfolio will be any better able to choose a better than average portfolio of investment company inventories .”

Mutual funds( or” financing fellowships “) has been established to procreate things easier for average people looks just like you and me. They rendered easy diversification, simplifying the entire investment process. Individual investors no longer had to build a portfolio of stocks. They could buy mutual fund shares instead, and the mutual-fund manager would take care of everything else. So handy!

But with 250 funds to choose from in 1960, the paradox of option was rearing its honcho once again. How could the average person know which store to buy?

When this paper was published in 1960, there is indeed nearly 250 mutual funds for investors to choose from. Today, there are nearly 10,000.

The solution suggested in this paper was an ” unmanaged investment company”, one that didn’t try to beat the market but only tried to match it.” While investing in the Dow Jones Industrial average, for instance, would mean foregoing the possibility of doing better than average ,” the authors wrote,” it would also mean tha the investor would be assured of never doing significantly worse .”

The paper too pointed out that an unmanaged money would render other benefits, including lower costs and mental comfort.

The authors’ conclusion will chime familiar to anyone who has ever read an article or bible praising the virtues of index funds.

” The evidence presented in this paper supports the view that the average investors in investment firms would be better off if a representative market average were followed. The paradoxical question that must be raised is why has the unmanaged investment company not come into being ?”

The Case for Mutual Fund Management

With the benefit of hindsight, we know that Renshaw and Feldstein were prescient. They were on to something. At the time, though, their intuition seemed far-fetched. Rebuttals weren’t long in coming.

The May 1960 issue of the Financial Analysts Journal included a counter-point from John B. Armstrong,” the pen-name of a husband who has spent many years in the security field and in studies and research and analysis of mutual funds .” Armstrong’s article — entitled” The Case for Mutual Fund Management” insisted vehemently against the notion of unmanaged investment companies.

” Market averages can be a hazardous instrument for evaluating investment management reactions ,” Armstrong wrote.

What’s more, he said, even if we were to grant the proposition of the earlier paper — which he wasn’t prepared to do –” this argument appears to be inaccurate on practical fields .” The bookkeeping and logistics for maintaining an unmanaged mutual fund would be a nightmare. The expenditures would be high. And besides, the technology( in 1960) to run such a store didn’t exist.

And besides, Armstrong said,” the relevant recommendations of an’ unmanaged fund’ has been tried before, and obtained unsuccessful .” In the early 1930 s, a type of proto-index fund was popular for a short period of time( accounting for 80% of all mutual fund investments in 1931 !) before being abandoned as “undesirable”.

” The careful and prudent Financial Analyst, likewise, realises full well that giving is an art — not a science ,” Armstrong concluded. For this reason — and many others — individual investors should be confident to buy into managed mutual funds.

So, merely who was the author of this segment? Who was John B. Armstrong? His real name was John Bogle, and he was an assistant manager for Wellington Management Company. Bogle’s article was nominated for industry awardings in 1960. People loved it.

The Secret History of Index Fund

Bogle may not have liked the relevant recommendations of unmanaged investment corporations, but other people did. A few of visionaries read the promise — but they couldn’t see how to set that promise into action. In his Investment News article about the secret history of indicator mutual funds, Stephen Mihm describes how the dream of an unmanaged fund became reality.

In 1964, mechanical designer John Andrew McQuown took a task with Wells Fargo heading up the “Investment Decision Making Project”, an attempt to apply technical principles to investing.( Remember: Just four years earlier, Bogle had written that” devoting is an art — not a science “.) McQuown and his team — which included a slew of tribes now famous in investing cliques — devote times trying to puzzle out the science of endowing. But they retained reaching dead ends.

After six years of work, the team’s biggest penetration was this: Not a single professional portfolio overseer could commonly overpower the S& P 500.

Mihm writes 😛 TAGEND

As Mr. McQuown’s team hammered out ways of tracking the index without incurring heavy fees, another University of Chicago professor, Keith Shwayder, approached the team at Wells Fargo in the hopes they could create a portfolio that tracked the part sell. This wasn’t academic: Mr. Shwayder was part of the family that owned Samsonite Luggage, and he is ready to positioned$ 6 million of the company’s pension resources in a new indicator fund.

This was 1971. At first, the team at Wells Fargo crafted a store that tracked all capitals sold on the New york stock exchange. This proved impractical — “a nightmare, ” one unit member later withdrawn — and eventually they created a fund that simply moved the Standard& Poor’s 500. Two other institutional index stores popped up around this time: Batterymarch Financial Management; American National Bank. These other firms helped promote the relevant recommendations of sampling: impounding a selection of representative capitals in a particular index rather than every single stock.

Much to the surprise and discouragement of skeptics, these early indicator funds wielded. They did what they were designed to do. Big institutional investors such as Ford, Exxon, and AT& T began changing pension money to indicator funds. But despite their predict, these brand-new stores remained inaccessible to the average investor.

In the meantime, John Bogle had become even more enmeshed in the world of active fund management.

In a Forbes article about John Bogle’s epiphany, Rick Ferri writes that during the 1960 s, Bogle bought into Go-Go investing, the vigorous following of outsized additions. Eventually, he was promoted to CEO of Wellington Management as he headed the company’s quest to make money through active trading.

The boom years soon progressed, however, and the market sank into slump. Bogle lost his power and his position. He persuaded Wellington Management to kind a new company — The Vanguard Group — to handle day-to-day administrative tasks for the larger firm. At the very beginning, Vanguard was explicitly not allowed to get into the mutual fund game.

About this time, Bogle dug deeper into unmanaged stores. He started to question his assumptions about the best interests of the active management.

During the fifteen years since he’d disagreed” the instance for mutual fund management”, Bogle had been an ardent, active fund director. But in the mid-1 970 s, as he started Vanguard, he was analyzing mutual fund performance, and he came to the realization that” active funds underperformed the S& P 500 indicator on an average pre-tax margin by 1.5 percentage. He too found that this shortfall was virtually identical to the costs incurred by fund investors during that age .”

This was Bogle’s a-ha moment.

Although Vanguard wasn’t allowed to manage its own mutual fund, Bogle located a opening. He persuaded the Wellington board to allow him to create an index fund, one that would be managed by an outside group of houses. On 31 December 1975, paperwork was filed with the S.E.C. to create the Vanguard First Index Investment Trust. Eight months later, on 31 August 1976, the world’s firstly public indicator store was launched.

Bogle’s Folly

At the time, most asset professionals believed index funds were a senseless mistake. In fact, the First Index Investment Trust was derisively announced “Bogle’s folly”. Nearly fifty years of history have proven otherwise. Warren Buffett- perhaps the world’s greatest investor- formerly said, “If a effigy is ever erected to honor the person who has done the most for American investors, the hands-down preference should be Jack Bogle.”

In reality, Bogle’s folly was ignoring the idea of index stores — even arguing against the idea — for fifteen years.( In another essay for Forbes, Rick Ferri interviewed Bogle about what he was thinking back then .)

Now, it’s perfectly possible that this” mystery biography” isn’t so secret, that it’s well-known among educated investors. Perhaps I’ve simply been blind to this info. It’s certainly true-blue that I haven’t read any of Bogle’s records, so perhaps he wrote about this and I simply missed it. But I don’t think so.

I do know this, nonetheless: On blogs and in the mass media, Bogle is usually bragged as the “inventor” of index funds, and that simply isn’t true-blue. That’s too bad. I feel the facts –” Bogle opposed indicator funds, then became their greatest endorse” — are more compelling than the apocryphal tales we stop parroting.

Note: I don’t doubt that I have some mistakes in this piece — and that I’ve left things out. If you have adjustments, please let me know so that I can rework the clause accordingly.

Read more: getrichslowly.org